on

Post 2 - DSpace and the Preservation Repository

This is the second in a series of posts on the development of GeoBlacklight at New York University. To see the first post and an overview of the series, visit here. The post was originally published in January 2016.

The role of an institutional repository in building collections

In the first post, we provided an overview of our collection process and technical infrastructure. Now, we begin our narrative with the first step: preservation within an institutional repository. Although we are not experts on the landscape of library repositories, we recognized early on that many schools are developing multi-purpose, centralized environments that attend to the interconnected needs of storage, preservation, versioning, and discovery. Furthermore, when it comes to collecting born-digital objects, every institution exists somewhere on a continuum of readiness. Some have a systematic, well-orchestrated approach to collecting digital objects and media of many kinds, while others have only a partially developed sense of how archival collections and other ad hoc born-digital items should exist within traditional library collections.

Stanford University is at the former end, it seems. The Stanford Digital Repository (SDR) is a multifaceted, libraries-based repository that allows for both collections (including archival materials, data, and spatial data) and researcher-submitted contributions (including publications and research data) to be housed together. Their repository attends to preservation, adopts a metadata standard, MODS, for all items, and imagines clear ways for content to be included within a larger discovery environment, SearchWorks. The SDR suggests a unifying process for providing access to many disparate forms of knowledge, some of which are accompanied by complex technological needs, and it facilitates the exposure of such items in ways that are useful to scholars and researchers of all kinds. See also the Purdue University Research Repository (PURR) for another good example of this model.

NYU is near the other end of this continuum of readiness, although this is changing with the advancement of our Research Cloud Services project. The closest thing we have currently is our Faculty Digital Archive (FDA), which is an instance of DSpace. As the name implies, the FDA was conceived as a landing-place for individual faculty research, such as dissertations, electronic versions of print publications, and other items.  More recently, we have started deploying it as a place to host and mediate purchased data collections for the NYU community, and we are encouraging researchers to submit their data as a way of fulfilling grant data management plan requirements. These uses anticipate the kind of function of the Stanford Data Repository, even if we haven’t arrived yet.

More recently, we have started deploying it as a place to host and mediate purchased data collections for the NYU community, and we are encouraging researchers to submit their data as a way of fulfilling grant data management plan requirements. These uses anticipate the kind of function of the Stanford Data Repository, even if we haven’t arrived yet.

Overview of Dspace and other options

Although NYU’s institutional repository status is in flux, we decided to begin with the FDA (DSpace) as we developed our spatial data infrastructure. In this case, it was a good decision to work within a structure that already existed locally. Fortunately, the specific tool used in the preservation component of the collection workflow is the least connected to GeoBlacklight of all our project components, which means it can be altered as larger changes take place within an institution. There are other options available aside from DSpace, most notably the Samvera project, a growing community that develops a robust range of resources for the preservation, presentation, and access of data. We won’t belabor this point, other than to say that if you’re working within a context that has no preservation repository in place, it is highly advisable to stand up an instance of DSpace, Samvera, or some other equivalent before beginning collection efforts.

Collection Principles

The concept of a preservation repository spurred our thinking about some important collection development principles at the onset. The first and most obvious is that preservation is vital. Agencies release data periodically, retract old files, and produce new ones. Data comes and goes, and for the sake of stability and posterity, it is incumbent on those creating access to data to be vested in the preservation of it as well. Thus, we will make an effort to preserve all data that we acquire, including public data.

Second, the repository concept demanded that we make a decision regarding the level of data at which we would collect. In other words, the concept forced us to define what constitutes a “digital object” and plan accordingly. For many reasons, we decided that the individual shapefile or feature class layer is the level at which we would collect. The layer as an object corresponds with the level of operation intrinsic to every GIS software, and it’s the way that data is already organized in the field. What this does mean, for instance, is that we will not create a single item record that bundles multiple shapefiles from a set or a collection. With only a few exceptions, there is a 1:1 correlation between each layer and each unique ID.

Adding Non-conventional Documentation or Metadata

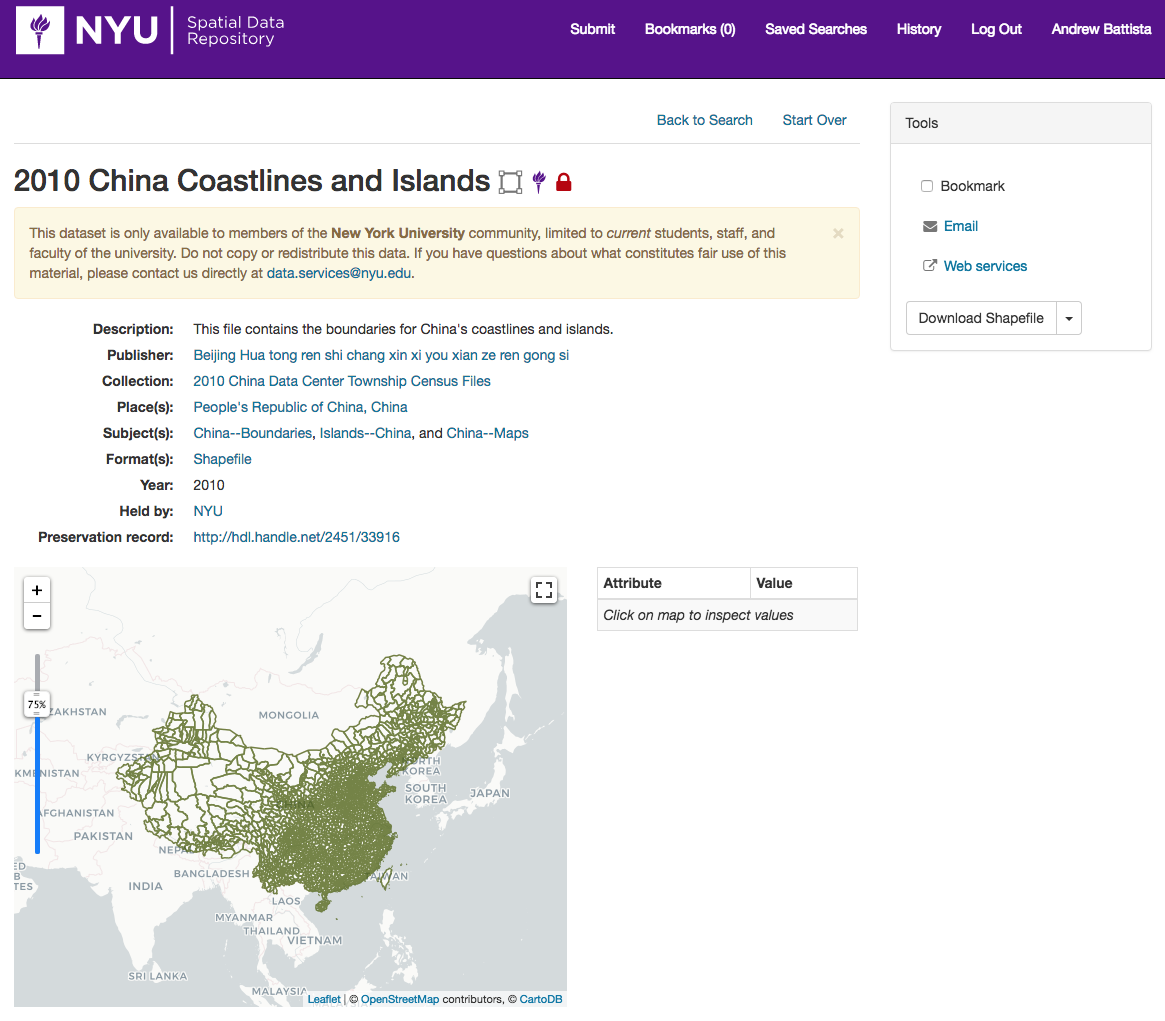

Beginning our collection by preserving a “copy of record” in the FDA also gave us the space and flexibility to pair proprietary data with its original documentation, particularly in cases in which documentation comes in haphazard or unwieldy forms. This record of 2010 China Coastlines and Islands is a good example.

A screenshot of an item in the FDA that is also in our spatial data repository.

A screenshot of an item in the FDA that is also in our spatial data repository.

We purchased this set from the University of Michigan China Data Center, and the files came with a rudimentary Excel spreadsheet and an explanation of the layer titles and meanings. Rather than trying to transform that spreadsheet into a conventional metadata format, we just uploaded the spreadsheet with the item record. Now, when the data layer is discovered, users have a direct pathway back to original documentation by clicking on the preservation record copy. In later iterations of the GeoBlacklight schema, documentation can be manifest on the tools layer by adding a valid URL in the dct_references field.

The Chicken-Egg Conundrum

The final (and most important) role of the repository model is that it generates a unique identifier which marks data in multiple places within the metadata schema and the technology stack behind it. This identifier applies to the item record in the repository, the layer in Geoserver, and the data file itself. However, given the workflow inherent in our process of collecting, the need for a unique identifier creates a classic chicken-egg scenario. In order to acquire an item, an item ID is required to create a metadata record for said item, yet without having made a “digital space” to store the item, we would not have the requisite “information” (i.e., the unique identifier) to create a metadata record for it. This is an easy problem to solve. We create an item in DSpace, get the unique identifier (the handle address), and then plug it into the GeoBlacklight metadata record. But as an ontological challenge and a workflow challenge, the process for generating unique identifiers can be something to think about.

Brief Snapshot of the Collection Model

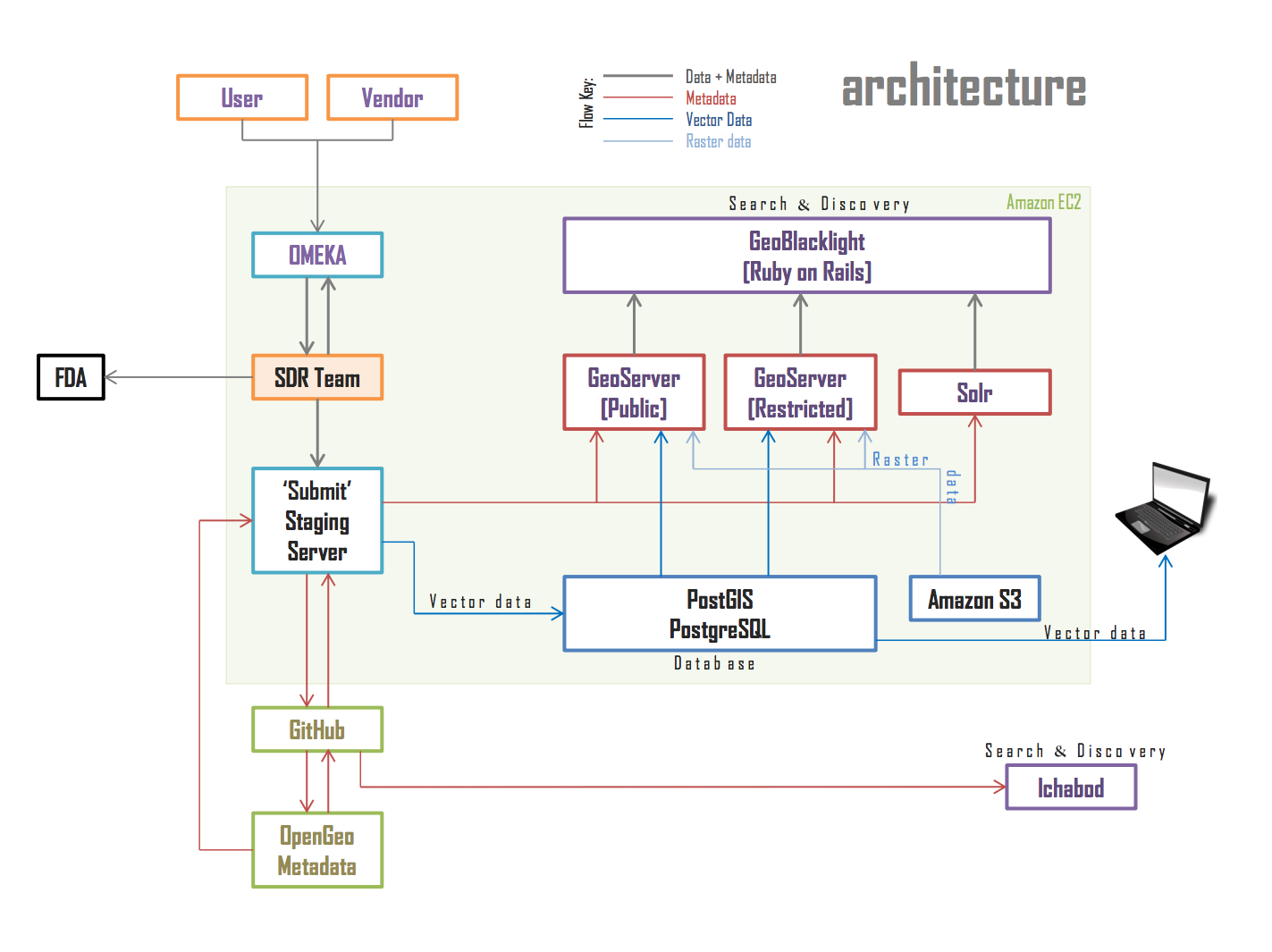

At this point, it makes sense to introduce one of our first project diagrams: a hand-drawn overview of our architecture and collection model. The section in the red box is what’s pertinent here.

An overview of NYU’s spatial data infrastructure

The collection process is follows. The decision to collect happens, and we add an item in the FDA, which generates a unique ID (a handle). Note that we have created two distinct collections within our DSpace: a collection for unrestricted data and a separate collection for private, restricted data. The generated handle, in turn, is integrated into several places in the GeoBlacklight metadata record, including the dct_references field, which triggers the direct file download within the GeoBlacklight application. We preserve both the “copy of record” and a re-projected version of the file on the same item record in the institutional repository, a decision we will explain later when we talk about the technology stack behind the project.

Batch Imports

Ingesting records at the batch level is possible thanks to the DSpace 5.x REST API. We simply count up how many total layers we want to import, generate that many handles, and then later go back and use a CSV to import the minimal metadata and data files themselves.

On using a Third-Party Unique Identifier

At various points in time during this project, we thought about the benefits of using a third-party persistent link generator in order to facilitate the collection process and mitigate the chicken-egg problematic. Fortunately, GeoBlacklight metadata is capacious enough to allow for several different kinds of unique identifier services. Stanford uses PURL, others use ARK, while still others use DOIs. We’ve chosen to remain with the unique ID minted by DSpace, at least for now.

Up Next: Creating GeoBlacklight Metadata Records

Everything we’ve discussed regarding preservation within an institutional repository is not directly implicated in the application of GeoBlacklight itself. However, it should go without saying that these preservation steps are the foundation of our spatial data infrastructure and help with the deployment of GeoBlacklight. In the next post, we will discuss the many ways to generate GeoBlacklight metadata as we collect spatial data.