on

Post 1 - GeoBlacklight at NYU: A Project Overview

This post was originally published in January 2016 and was designed to be a guide for setting up a Spatial Data Infrastructure using GeoBlacklight. I’ve placed them here and have made slight updates to reflect recent developments in our project and other projects surrounding this one at NYU.

Getting Started with GeoBlacklight

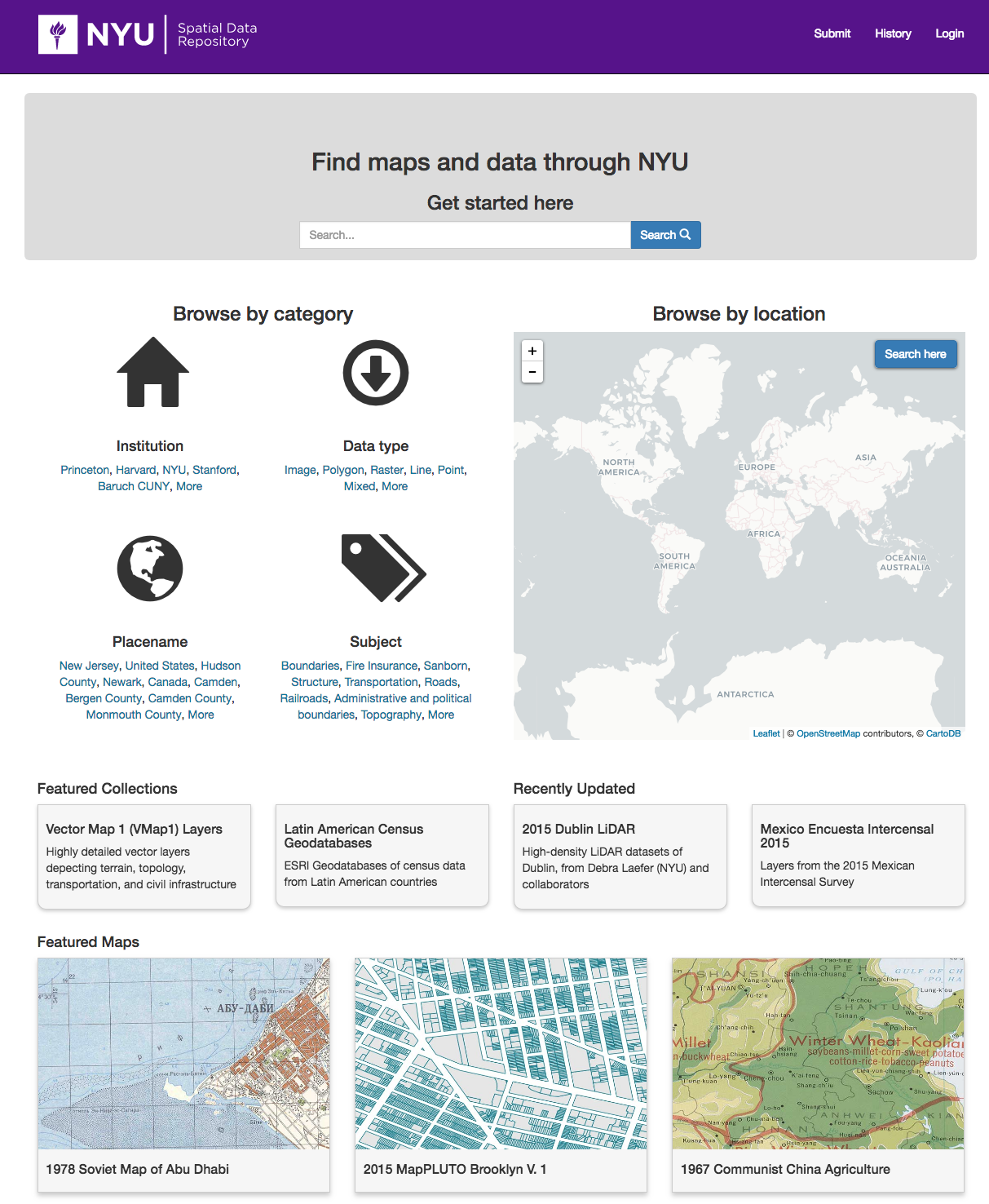

In January, 2016, the GIS team at NYU’s Data Services released an advanced beta version of GeoBlacklight, a search and discovery platform for geospatial data. This release comes after a year of developing a spatial data infrastructure (SDI) that includes a holistic model for discovery, storage, and preservation of spatial data. NYU’s instance of GeoBlacklight allows users to preview layers, explore attribute tables associated with points and geometries, export datasets directly into Carto, and download data in Shapefile, KML, or GeoJSON format.

This is the first in a series of posts on developing a SDI that features GeoBlacklight as a discovery mechanism. These posts describe our previous year at NYU, a time in which we went from having almost no familiarity with GeoBlacklight to instituting a near-production level spatial data infrastructure.

GeoBlacklight at NYU is part of a larger spatial data infrastructure and is based on the work of Stanford University Libraries. Stanford released Earthworks, a local deployment of GeoBlacklight, in 2015, and the university’s spatial data exists within a larger context of an institutional repository, or the Stanford Digital Repository. Many thanks to Jack Reed, Darren Hardy, Bess Sadler, and Kim Durante at Stanford and Eliot Jordan at Princeton. They have been more than generous in sharing their progress and advice with us.

Additionally, throughout the year we have participated in and co-led several sessions on GeoBlacklight metadata, including a workshop at the 2015 DLF. Still, we wanted to detail as much of our narrative as possible, both for the benefit of people within our own institution and for others who are developing spatial data infrastructures at their own institutions. We’ve found that while very good documentation on deploying GeoBlacklight exists, there is less information about the parts of the collection workflow that surround GeoBlacklight, or on the ways in which a spatial data collection can be integrated into the environment of larger library collections, or what Durante and Hardy call “durable, digital library assets”.

However, we must start with a disclaimer. We do not mean to insinuate that we have discovered the only or best way to facilitate spatial data collections or to author metadata; instead, much of this narrative represents a project that is still in process. We just want to share what has worked for us and encourage others in the GeoBlacklight community to develop with GeoBlacklight. We would also like to solicit feedback from the broader GIS and library technology community, particularly those who are attending the 2016 Geo4Lib meeting at Stanford University. Also, click here for the 2018 meeting schedule.

Background at NYU

Prior to the deployment of GeoBlacklight, NYU provided access to collected geospatial datasets in two ways. While on campus, users could connect directly from ArcMap or QGIS to an Oracle database, which stored our collection. Additionally, a simple web interface allowed NYU users (either on or off campus) to browse text-only representations of the datasets within the library’s collections, and download zipped shapefiles. Given the configuration of the system, very little metadata was exposed to the user on the web interface (and virtually none in the direct-connection method). Thus, users also had no ability to do a spatial search, preview a layer (graphically or by querying datafields), or download data in a format other than a shapefile.

Furthermore, it became highly impractical to add new spatial data to our collection, as we had no immediate access to the Oracle database. And what little spatial data collection that had taken place existed largely outside of the flow for collecting and discovering other born-digital items at NYU. Given the interest in developing a more feature-rich GIS discovery platform, which coalesces with NYU’s ongoing Research Cloud Services project, we started considering options for building the requisite infrastructure and formulating a model for data accessioning and preservation.

We prioritize open-source, library community-led solutions, so we looked most closely at OpenGeoPortal and GeoBlacklight. GeoBlacklight quickly became the most attractive discovery interface for a variety of reasons. It emphasizes a robust metadata schema that facilitates library discovery, it is accompanied by an active developer community and is increasingly being adopted among peer institutions, it has a light-weight and easily expandable Ruby and JavaScript codebase, and it seamlessly integrates with many external technologies NYU Libraries are developing or implementing (Solr, IIIF, and GeoServer are a few examples).

We also made the decision to experiment with developing on a “cloud” platform. Originally, we made this choice because using a vendor like Amazon Web Services would allow us to spin up an entire development ecosystem very quickly and affordably. This approach, more than anything else, allowed us to make rapid progress on this project. The ability to play around, break things, and gain a more sophisticated understanding of different software interconnections was invaluable and is an important part of our development narrative.

Key Elements of Stanford’s Model

We modeled the redevelopment of our spatial data infrastructure on Earthworks and considered how Stanford’s deployment of GeoBlacklight, called EarthWorks, links up with their Library’s broader digital repository environment. The two pivotal pieces of information for us were a July, 2014 code4lib article on GeoBlacklight metadata, and a December, 2014 conference call with a few people at Stanford. The crucial idea that emerged from our reading and conversations is that spatial data collection should begin with preservation. There are many good reasons to do this, as will become evident as we describe our project. But for now:

- Free and open data sources come and go so it’s important to preserve them

- A platform that takes care of preservation also allows for the retention of accompanying documentation in ways that a discovery platform like GeoBlacklight may not, although this has changed as the project has developed over time

- A preservation platform ensures that the original data format or map projection is saved, in case it is ever discovered that one of the derived editions is deficient

This focus on preservation dovetails with another important point: that collection should be oriented around the Fedora Digital Object Model. As we found out, a “digital object” can mean a lot of different things to different people, so following Stanford’s lead in defining digital objects and building a collection of them was highly instructive.

Overview of Posts

This post is an overview of a large, multifaceted collection workflow that relies on several elements of NYU Libraries. The goal is to introduce those who are developing a collection workflow or a Spatial Data Infrastructure from scratch to the technologies and implementations associated with the GeoBlacklight project. Here is an outline of the posts.

Post 1 – GeoBlacklight at NYU: A Project Overview (this post)

- Introduction to the Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) at NYU

Post 2 – DSpace and the Institutional Repository: Preservation and the Spatial Data Infrastructure

- How to design a collection workflow that begins with preservation

- How to structure a spatial data collection around existing library infrastructure

Post 3 – Creating GeoBlacklight Metadata Records

- How to create GeoBlacklight metadata records from scratch

- What to do with GeoBlacklight metadata records once they are created

- How to anticipate researcher-generated contributions

Post 4 – The Technology Stack: Amazon Web Services Products & Open Source GIS

- How to navigate Amazon Web Services product offerings

- How to deploy products to test out a collection model

- How to take advantage of the FOSS community

Post 5 – How to Stay Connected to the GeoBlacklight Community

- Where are GeoBlacklight discussions happening?

- How can new participants join in and influence the community?

Post 6 – Current Needs, Possible New Directions

- Establishing a metadata application profile

- Evolving the GeoBlacklight Schema

- New scholarship